Top-down prescription or participatory

culture: Official terminology in the internet age

Merryn Davies-Deacon, Queen’s University Belfast

Mediatisation

- Media are dominant in conveying communications and media channels have the potential to transform the messages they carry

- Mediatisation research considers how everyday life is saturated by media and how this can lead to social/cultural change (Hepp, 2020:4)

Participatory culture

- Growing “involvement of users, audiences, consumers and fans in the creation of culture and content” (Fuchs, 2014:52)

- Lenihan 2014: investigates the development of Facebook’s Irish-language interface

- Some argue that participatory culture leads to increased democratisation (Fuchs 2014:52–53)

- But “internet culture … is to a large extent organised, controlled and owned by companies” (Fuchs, 2014:52)

- Less problematic in the case of language planning bodies?

Language planning and online language use

- “Increasing interest in the agents of standardisation” (Ayres-Bennett 2021:48)

- Emerging processes of “destandardisation” (Ayres-Bennett 2021:49) – indicating valorisation of formerly devalued varieties

- Need to understand the interplay between prescription and usage (Ayres-Bennett 2020)

- Online language practices “can be hard to classify in terms of established dichotomies (e.g. top-down/bottom-up)” (Blommaert et al., 2009:204)

- Room for more democratic participation in language planning processes?

The study

- Three language planning bodies:

- French in France (Commission d’enrichissement de la langue française)

- French in Quebec (Office québécois de la langue française)

- Breton in Brittany (Office public de la langue bretonne)

- Organisations’ own websites: not constrained by the structures of social media

- Different interactions with (perceived) dominant languages

- Different histories of officialisation and standardisation

Questions

- How do these bodies use digital technology to communicate their terminological prescriptions?

- What is the role of public participation in this?

- Do differences in participatory mechanisms among the three contexts reflect the different situations of the languages and their speakers in each one?

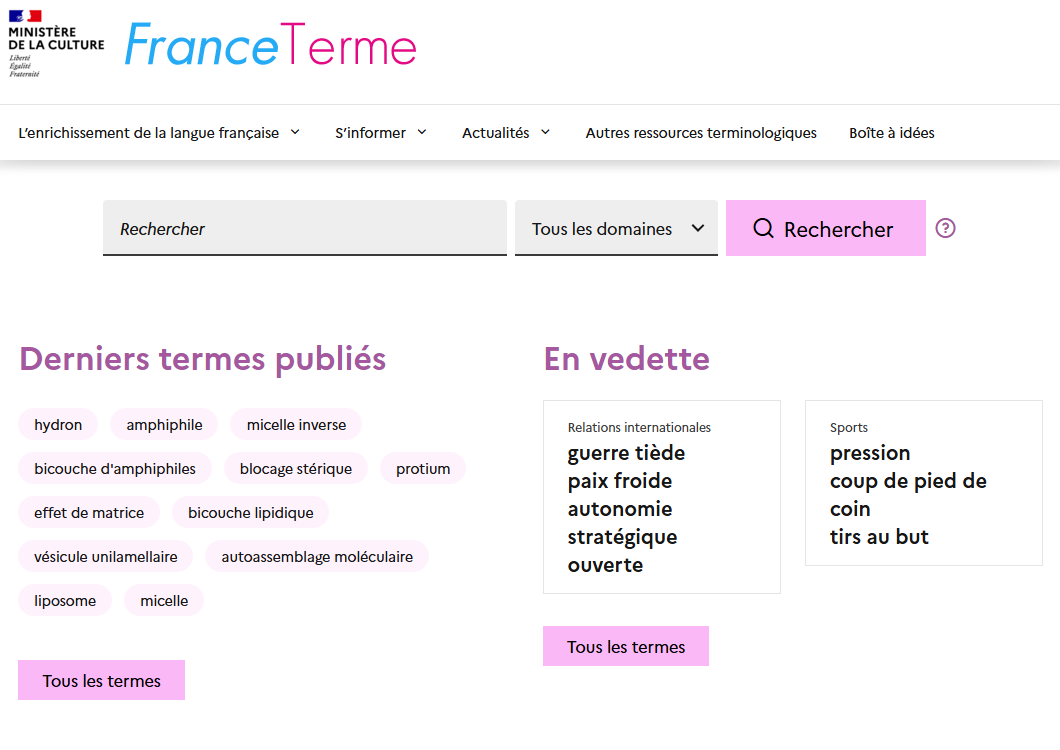

France: FranceTerme

- Operated by the Délégation à la langue française et aux langues de France to communicate the terminology recommended by the Commission à la langue française

- Terms are also published in the Journal officiel

- Intended for civil servants, who are required to use official terms “en lieu et place de termes étrangers” (DGLFLF 2018:7)

- But they suggest that FranceTerme will be of interest to “tous ceux qui, curieux de la langue française et de son évolution, souhaitent savoir comment nommer les notions et réalités nouvelles qui ne cessent d’apparaître dans les sciences et les techniques” (ibid.)

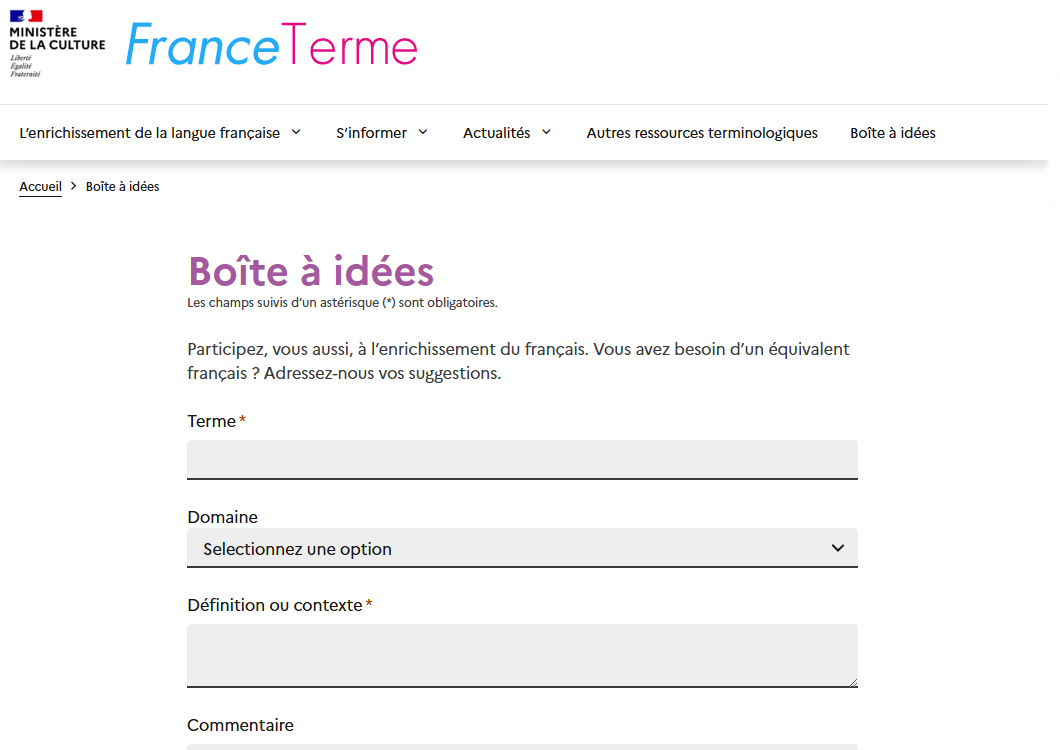

User participation on FranceTerme

- Boîte à idées – on the site since FranceTerme’s creation in 2007

- Users are asked to provide “foreign” terms that need to be translated into French: “Vous avez besoin d’un équivalent français ?”

- A monitoring mechanism (DGLFLF 2024:21)

User participation on FranceTerme

- 88 out of 300 new terms published in 2023 were brought to the Commission’s attention through the Boîte à idées

- Délégation 2023 report gives 35 examples, 5 of which are in French (DGLFLF 2024) – suggesting French words were supplied by the users in these cases?

- According to Délégation reports, all suggestions were initially passed to the Commission, although this has become more selective (113 out of 210 suggestions in 2022 – DGLFLF 2023:47–48)

- Some terms have already been identified

- Others do not pertain to specialist terminology – users’ own coinages (samdim, aviaceau)

Quebec: Office québécois de la langue française

- Wider remit than language planning bodies in France: also monitors compliance with the Charte de la langue française

- Development of a specific Quebecois norm

- Like in France, official terms are intended for government documents, but available to the public: “le contenu de la Vitrine linguistique est d’abord destiné à la population québécoise” (

https://vitrinelinguistique.oqlf.gouv.qc.ca/politique-editoriale)

- Accompanied by resources on grammar, orthography, and style

- Grand dictionnaire terminologique also includes many items of non-specialist vocabulary

- Contact form with an option for “suggestion d’ajout”, but no specific mechanism for soliciting suggestions

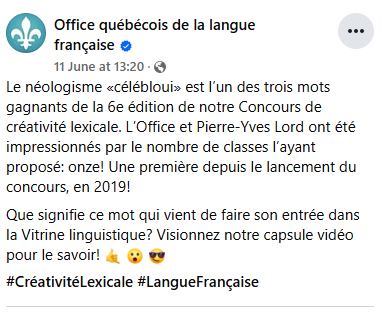

Concours de créativité lexicale

- Targeted at school classes

- Three winning entries are added to the Grand dictionnaire each year

- English terms are proposed by the Office for translation – the opposite of FranceTerme’s Boîte à idées

- Not a predominantly online process

- Focus on young people as the future of the language, but still heavily controlled by the Office

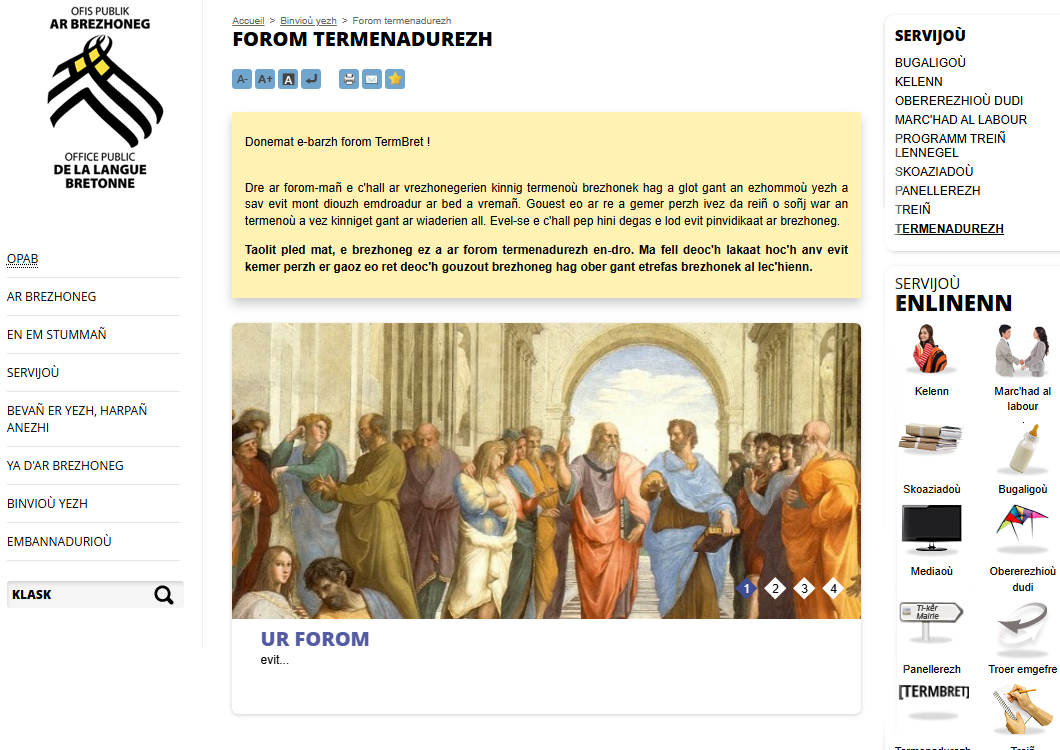

Breton: Office public de la langue bretonne

- Like the Quebecois Office, a wider remit than corpus planning

- Benefits from local government funding, but not a government body; a public institution since 2010

- Not all terms are subjected to such rigid processes

- TermOfis gives officially recommended terms in French and Breton (no definitions)

- Interface is available in both Breton and French

Le forum terminologique

- Around two French terms per month are selected and sent to users via mailing list

- Two phases:

- Suggestion of Breton equivalents

- Voting on suggestions

- Low participation rate – suggests speakers would rather be prescribed to

- Hard to discern boundary between terminology and general lexis

Comparison

- Similar structure involving staff and committees of experts

- Sense of hierarchy between experts and the public

- Participation takes place but is heavily regulated

- Tension between accepting user-generated content and following standards (Breton Office follows ISO terminology standards including consistency, brevity, etc.)

- Different beliefs about the role of the public:

- Quebec: emphasis on creativity and the role of younger generations

- France: Commission positioned as the authority; participatory element framed as users asking them for advice (see also Humphries 2024 on the Académie française)

- Breton: participatory element is more developed and provides transparency in a historically contentious field

Conclusion

- Co-creation of language policy is enacted differently across contexts

- Organisations maintain their authority and can harness participatory elements as a way of monitoring usage

- Can foster interest in terminology among members of the public

- Not disrupting the top-down/bottom-up dichotomy, but using bottom-up input to inform and enhance top-down prescriptions

References

- Ayres-Bennett, W. (2020). From Haugen’s codification to Thomas’s purism: Assessing the role of description and prescription, prescriptivism and purism in linguistic standardisation. Language Policy 19, 183–213.

- Ayres-Bennett, W. (2021). Modelling language standardisation. In W. Ayres-Bennett & J. Bellamy (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of language standardisation (pp. 27–64). Cambridge University Press.

- Blommaert, J., Kelly-Holmes, H., Lane, P., Leppänen, S., Moriarty, M., Pietikäinen, S., & Piirainen-Marsh, A. (2009). Media, multilingualism and language policing: An introduction. Language Policy 8, 203–207.

- Délégation générale à la langue française et aux langues de France (2018). L’enrichissement de la langue française. Ministère de la culture.

- Délégation générale à la langue française et aux langues de France (2023). Rapport annuel 2022 de la Commission d’enrichissement de la langue française. Ministère de la culture.

- Délégation générale à la langue française et aux langues de France (2024). Rapport annuel 2023 de la Commission d’enrichissement de la langue française. Ministère de la culture.

- Fuchs, C. (2014). Social media: A critical introduction. SAGE Publications.

- Hepp, A. (2020). Deep mediatisation. Routledge.

- Humphries, E. (2024). Comparing the prescriptivism of nineteenth- and twenty-first-century language experts in France. In J. Carruthers, M. McLaughlin, & O. Walsh (Eds.), Historical and sociolinguistic approaches to French (pp. 276–296). Oxford University Press.

- Lenihan, A. (2014). Investigating language policy in social media: Translation practices on Facebook. In P. Seargeant & C. Tagg (Eds.), The language of social media: Identity and community on the internet (pp. 208–227). Palgrave Macmillan.